Those who come bearing warnings are rarely popular. Cassandra didn’t do herself any favors when she told her fellow Trojans to beware of the Greeks and their wooden horse. But, with financial markets facing unprecedented turbulence, it’s important to take a hard look at economic realities.

Analysts agree markets face serious headwinds. The International Monetary Fund has forecast that one-third of the world’s economy will be in recession in 2023. Energy is in high demand and short supply, prices are high and rising and emerging economies are coming out of the pandemic in shaky conditions.

There are five fundamental — and interlinked — issues that spell trouble for asset markets in 2023, with the understanding that in uncertain environments, there are no clear choices for investors. Every decision requires trade-offs.

Net energy shortages

Without dramatic changes in the geopolitical and economic landscape, fossil fuel shortages look likely to persist through next winter.

Russian supplies have been slashed by sanctions related to the war in Ukraine, while Europe’s energy architecture suffered irreparable damage when a blast destroyed part of the Nord Stream 1 pipeline. It’s irreparable because new infrastructure takes time and money to build and ESG mandates make it tough for energy companies to justify large-scale fossil fuel projects.

Related: Bitcoin will surge in 2023 — but be careful what you wish for

Meanwhile, already strong demand will only increase once China emerges from its COVID-19 slowdown. Record growth in renewables and electric vehicles has helped. But there are limits. Renewables require hard-to-source elements such as lithium, cobalt, chromium and aluminum. Nuclear would ease the pressure, but new plants take years to bring online and garnering public support can be hard.

Reshoring of manufacturing

Supply chain shocks from the pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have triggered an appetite in major economies to reshore production. While this could prove a long-term boon to domestic growth, reshoring takes investment, time and the availability of skilled labor.

In the short to medium-term, the reshoring of jobs from low-cost offshore locations will feed inflation in high-income countries as it pushes up wages for skilled workers and cuts corporate profit margins.

Transition to commodities-driven economies

The same disruptions that triggered the reshoring trend have led countries to seek safer — and greener — raw materials supply chains either within their borders or those of allies.

In recent years, the mining of crucial rare earth has been outsourced to countries with abundant cheap labor and lax tax regulations. As these processes move to high-tax and high-wage jurisdictions, the sourcing of raw materials will need to be reenvisioned. In some countries, this will lead to a rise in exploration investment. In those unable to source commodities at home, it may result in shifting trade alliances.

We can expect such alliances to mirror the geopolitical shift from a unipolar world order to a multipolar one (more on that below). Many countries in the Asia Pacific region, for instance, will become more likely to prioritize China’s agenda over that of the United States, with implications for U.S. access to commodities now sourced from Asia.

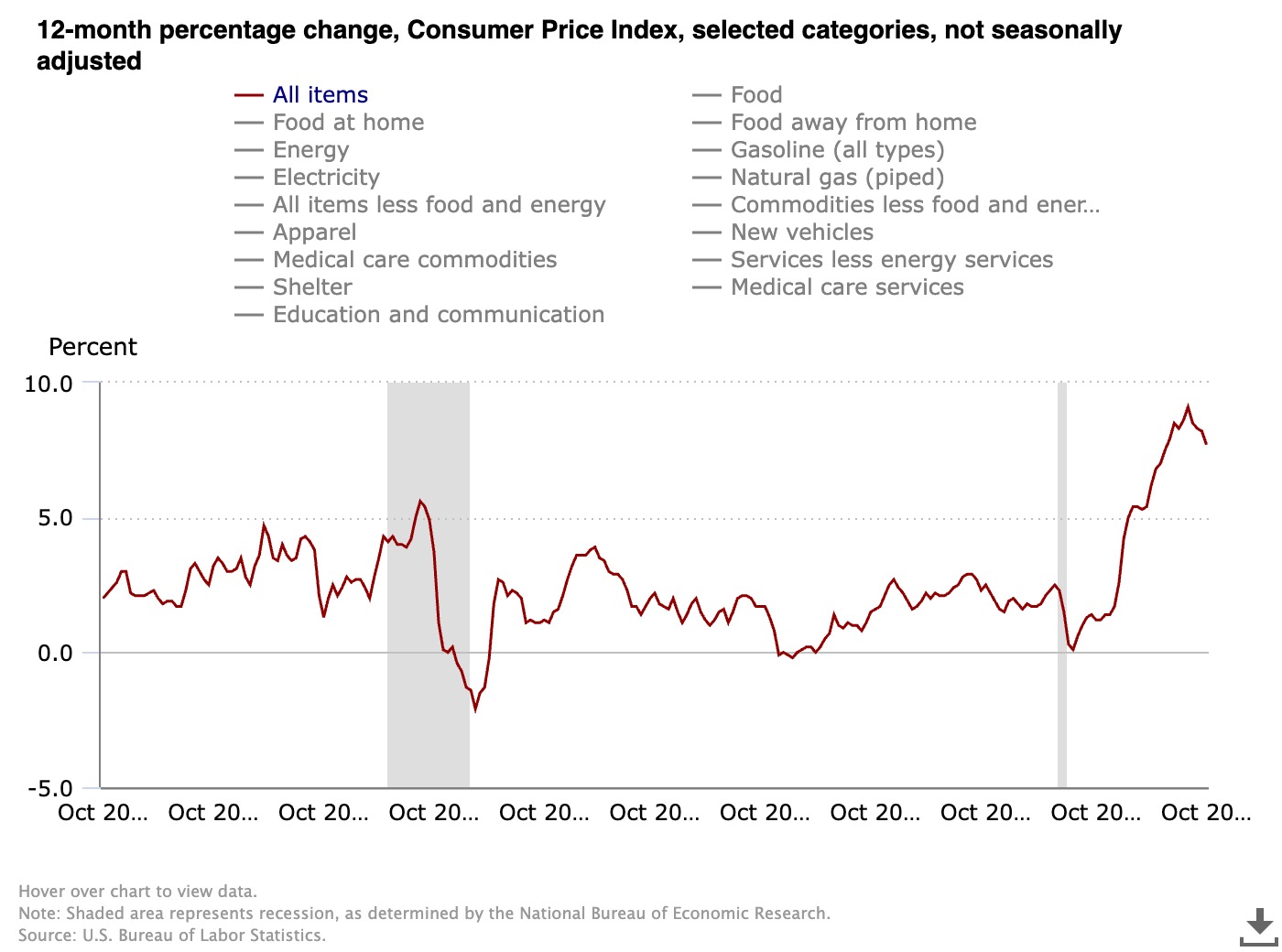

Persistent inflation

Given these pressures, inflation is unlikely to slow anytime soon. This poses a huge challenge for central banks and their favored tool for controlling prices: interest rates. Higher borrowing costs will have limited power now we have entered an era of secular inflation, with supply/demand imbalances resulting from the unraveling of globalization.

Past inflationary cycles have ended when prices rose to a point of unaffordability, triggering a collapse in demand (demand destruction). This process is straightforward when it comes to discretionary purchases but problematic when necessities such as energy and food are involved. Since consumers and businesses have no alternative but to pay the higher costs, there is limited scope to ease upward pressure, particularly with many governments subsidizing consumer purchases of these staples.

Accelerating decentralization of key institutions and systems

This fundamental shift is being driven by two factors. First, a realignment in the geopolitical world order was touched off by broken supply chains, tight monetary policy, and conflict. Second, a global erosion of trust in institutions caused by a chaotic response to COVID-19, economic woes and rampant misinformation.

The first point is key: Countries that once looked to the United States as an opinion leader and enforcer of the order are questioning this alignment and filling the gap with regional relationships.

Meanwhile, mistrust in institutions is surging. A Pew Research Center survey found that Americans are increasingly suspicious of banks, Congress, big business and healthcare systems — even against one another. Escalating protests in the Netherlands, France, Germany and Canada, among others, make clear this is a global phenomenon.

Related: Get ready for a swarm of incompetent IRS agents in 2023

Such disaffection has also prompted the rise in far-right populist candidates, most recently in Italy with the election of Georgia Meloni.

It has likewise provoked growing interest in alternative ways to access services. Homeschooling spiked during the pandemic. Then there’s Web3, forged to provide an alternative to traditional systems. Take the work in the Bitcoin (BTC) community on the Beef Initiative, which seeks to connect consumers to local ranchers.

Historically, periods of extreme centralization are followed by waves of decentralization. Think of the disintegration of the Roman Empire into local fiefdoms, the back-to-back revolutions in the 18th and early 19th century and the rise of antitrust laws across the West in the 20th. All saw the fragmentation of monolithic structures into component parts. Then the slow process of centralization began anew.

Today’s transition is being accelerated by revolutionary technologies. And while the process isn’t new, it is disruptive — for markets as well as society. Markets, after all, thrive on the ability to calculate outcomes. When the very foundation of consumer behavior is undergoing a phase shift, this is increasingly hard to do.

Taken together, all these trends point to a period where only the careful and opportunistic investor will come out ahead. So fasten your seatbelts and get ready for the ride.

Joseph Bradley is the head of business development at Heirloom, a software-as-a-service startup. He started in the cryptocurrency industry in 2014 as an independent researcher before going to work at Gem (which was later acquired by Blockdaemon) and subsequently moving to the hedge fund industry. He received his master’s degree from the University of Southern California with a focus in portfolio construction/alternative asset management.

This article is for general information purposes and is not intended to be and should not be taken as legal or investment advice. The views, thoughts and opinions expressed here are the author’s alone and do not necessarily reflect or represent the views and opinions of Cointelegraph.